Compression Routes in Chiang Mai: Move More, Waste Less

The Insight

Compression routes in Chiang Mai cut transfer time by chaining only high-signal segments.

Operationally: delete every segment that does not move you cleanly toward your target node.

The Principle

Compression = fewer mode switches, fewer uncertainty points, tighter time variance around a known median.

In engineering terms, each transfer is a failure surface, so the design goal is minimizing joins.

A compression route therefore prioritizes stable, repeatable links over theoretically faster but volatile options.

Think less in “shortest distance” and more in “fewest state changes under local constraints.”

In Northern Thailand, state change usually means swapping drivers, vehicles, road classes, or coordination methods.

Every swap adds cognitive load, negotiation overhead, and failure probability, even if the map shows a shorter line.

The Local Reality

Chiang Mai Province runs on a mixed network: red songthaews, blue buses, minivans, private trucks, and scattered motorcycle taxis.

Compression routing starts by mapping which pieces are actually clock-stable, not just physically present.

The Arcade Bus Station to Mae Sariang green bus line is one such stable spine with predictable departures.

By contrast, many backhaul songthaew legs from mountain villages are opportunistic, not schedule-based, and therefore noisy.

On routes like Chiang Mai → Mae Wang → Khun Wang → Ban Mae Sapok, the weakest link is often the last truck hop.

If that last hop depends on chance-loading from local farms, your time variance explodes even when distance is small.

Guides around Doi Inthanon and Mae Chaem know this and often pre-book full pickup loops instead of stacking public segments.

They are trading slightly higher upfront cost for a hard cap on uncertainty and idle time.

In practice, locals treat Highway 108 and 107 as compression backbones and treat minor roads as controlled side branches.

That means your design space is not infinite; the stable graph is actually a limited set of tested spines plus local stubs.

The Decision Point

The main decision: are you optimizing for variance control or raw cost per kilometer.

If time variance must stay narrow, you compress on the most reliable backbone, even if it looks indirect.

Example: Chiang Mai → Pai → Soppong → Mae Hong Son looks scenic but adds multiple high-friction passes and van changes.

For compression, many local operators instead run Chiang Mai → Mae Sariang → Mae Hong Son along 108, one spine, fewer joins.

Another decision point: when to pay for a private transfer to eliminate a weak public-link node entirely.

If a single unscheduled cliff-edge segment (like Mae Chaem → remote Hmong village) can collapse your plan, you over-spec it.

That might mean booking a known driver from Mae Chaem market, even if a passing truck is statistically likely.

You treat this like adding redundancy for a critical component in a mechanical system.

Compression logic also decides what not to do, like skipping a side valley if it forces an overnight just to catch a morning truck.

Here, the cost is not money or distance but wasted calendar blocks and unnecessary sleeping points.

The Compression Move

The core move is to pick one durable trunk route, then pack value along that trunk instead of hopping trunks.

For Chiang Mai, the main trunks are: 107 north to Fang, 108 south-west to Mae Sariang, and 1009/108 up to Doi Inthanon zones.

A compression design for “mountain treks + Karen villages + minimal transfers” might lock 108 as the trunk.

Then you structure: Chiang Mai → Mae Sariang by bus, fixed base with one guide, radial day trips by truck.

Instead of: Chiang Mai → Chom Thong → Mae Chaem → Khun Yuam → Mae Sariang with separate bookings and uncertain songthaews.

This swaps four coordination points for one, which is a compression win even if the paper distance is similar.

Physics analogy: you route through a main beam and bolt smaller loads to it, rather than welding many thin beams together.

Local analogy: guides in Ban Mae Sam Laep run fixed pickup times from Mae Sariang and attach side activities to that anchor.

Your map then becomes a simple schema: one backbone line, short predictable branches, clear re-entry points, zero dead ends.

Dead ends in this context are any legs where return timing depends on low-probability traffic or unclear driver incentives.

Compression removes those dead ends by either upgrading transport mode or relocating your base to a higher-signal village.

Example: shifting from an isolated homestay up a deteriorated side road to Mae La Noi town to regain bus access on 108.

The Principle

System-level: minimize entropy inflow at each trip node, not just travel time on each edge.

Every new driver, language jump, or “maybe truck” node is an entropy injector into your route.

Compression routes in Chiang Mai work because they rely on node types that locals also defend for their own reliability.

Arcade Bus Station, Chang Phuak bus stop, Chom Thong market, Mae Sariang bus terminal, and Pai bus station are prime examples.

These nodes have aligned incentives: vendors, students, and traders all need them to run on rough time anchors.

When you design around such nodes, you are riding existing demand structures rather than fighting them.

Reducing mode count multiplies the benefit of those nodes, because each stable node now covers a bigger share of your graph.

It is similar to reducing interfaces in a software stack; fewer interfaces mean fewer integration bugs.

The Chiang Mai hills add load constraints: steep grades, rain season washouts, and fog on passes like Pai–Mae Hong Son.

Compression routes pre-accept these slowdowns on one main segment rather than scattering risk across many side roads.

The Local Reality

Real guides and drivers already run compression logic informally because their income depends on on-time completion.

A driver running Khun Yuam → Mae Chaem → Chiang Mai in one push will usually time it to avoid peak fog blocks on 1263.

Village hosts in places like Ban Huai Hea know typical songthaew timings to Mae Sariang and advise guests to sync with them.

When guests ignore that and chase extra side trips, their exit route complexity jumps and reliability drops.

Chiang Mai-based trekking outfits that last usually standardize on a small set of “known good” loops.

They use the same drivers, same fuel stops, same weather windows, and same village connections repeatedly.

This is route compression over time: they compress uncertainty by repetition until edge cases become known patterns.

Your compression route design borrows from their learned patterns, rather than improvising from map tiles and reviews.

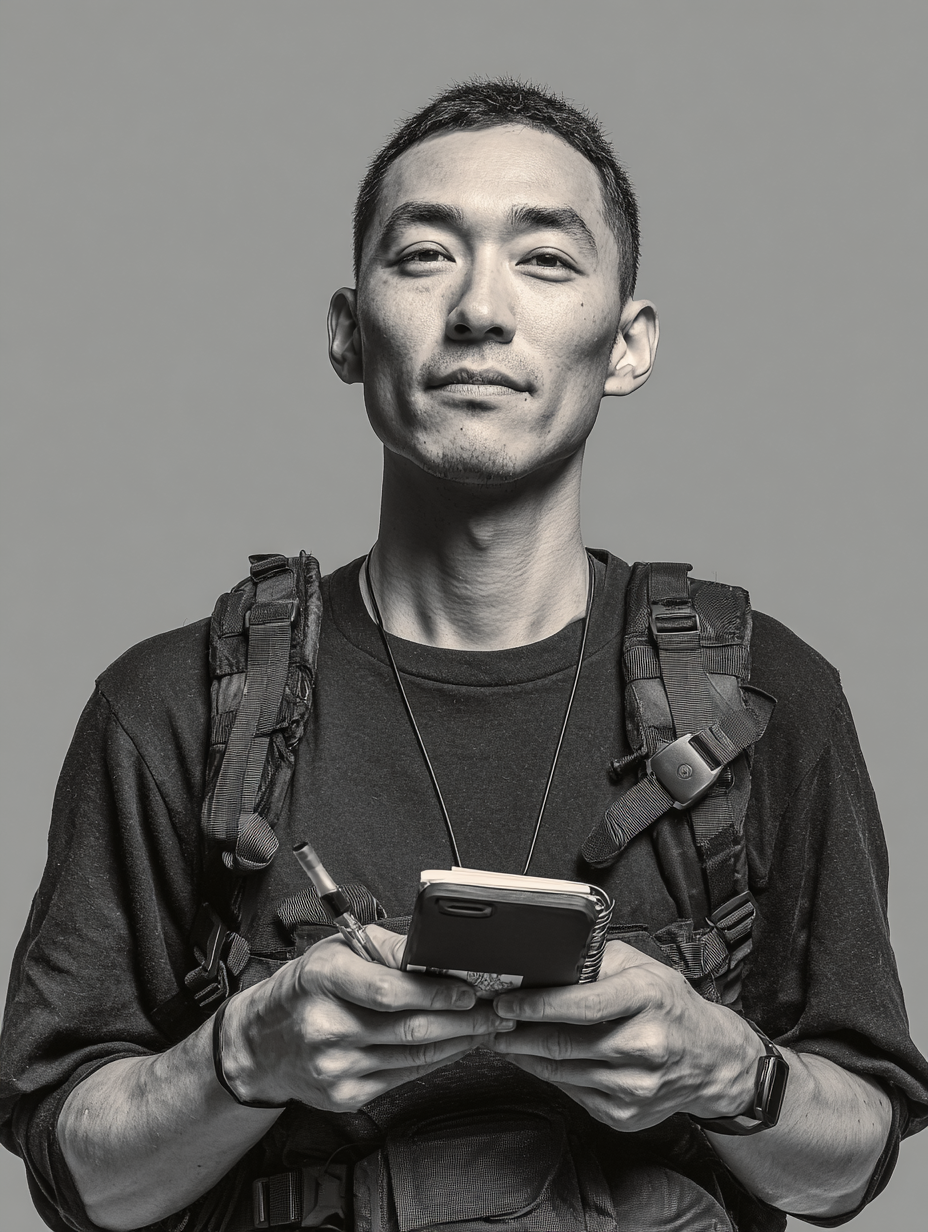

Waykeeper’s non-OTA stance aligns with this, since compression routing needs direct lines to humans, not generic listings.

Actual phone numbers, known drivers, and named homestays matter more than polished photos or vague route descriptions.

The Decision Point

Before locking your Chiang Mai route, you choose your tolerance for uncertainty and your base trunk.

Question one: “Do I accept waiting with no clear upper bound at rural nodes.”

If the answer is no, you stay on 108 or 107 or 1009 spines and keep side trips time-boxed and driver-backed.

Question two: “Is my primary constraint money, calendar days, or mental load.”

If money is tight but time is loose, you can tolerate more side hops and soft timing and still survive failures.

If calendar is tight, you compress ruthlessly: fewer beds, fewer drivers, fewer buses, more repeat paths.

You might run Chiang Mai → Mae Sariang → Mae Hong Son and back on the same 108 corridor, reusing known nodes twice.

This generates learning; your outbound trip debugs your return, which is compression across iterations.

If mental load is the constraint, you pre-book only the hard edges and leave the soft edges with wide buffers.

That might mean fixed buses and drivers but flexible walking or cycling around base towns like Pai or Mae Sariang.

The Compression Move

Practically, you compress by running an if/then filter on every planned segment.

If a segment has unclear schedule, unclear exit, or unclear fallback, you either strengthen it or cut it.

Strengthening might mean: pre-arranged pickup from a village, a written price, a defined time window, and a backup contact.

Cutting means you instead allocate that time to a higher-signal area along your trunk route.

Example: drop a speculative village visit off highway 1263 and instead spend those hours in Mae Chaem, where buses and drivers cluster.

You trade shallow spread for deeper engagement in fewer nodes, which is still travel, just more controlled.

Each compression move is ✂️ on one dimension: nodes, transfers, or uncertainty types.

You measure the outcome in fewer unknowns per day, not in number of places “covered.”

In Chiang Mai’s terrain, this also reduces exposure to road incidents because you are not chasing marginal, low-used roads.

Less exposure time on weak surfaces = lower probability of significant disruption.

The Closing Truth

Reliable travel in Chiang Mai comes from compressing routes until only strong links remain.

Related blogs

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur. Adipiscing eget risus tempus facilisis scelerisque vitae consectetur vitae. Amet faucibus venenatis donec mattis.